This is part five in a series of profiles where the subject was persecuted for the crime of telling the truth, when it would’ve been way more convenient to lie.

When we face trials or tribulations in our lives, it is so much easier in the long run to just tell the truth. As a practical life lesson, when we lie it begins a snowball rolling down a hill, as we make the next lie to cover for the previous lie the snowball gets bigger and so on, and so forth. We quickly realize if we would’ve told the truth in the first place it would’ve been much easier to manage, but now that we’ve started it seems too late to turn back, things spiral and the snowball grows and grows. This ends in crisis and devastation. In spite of this, there is a pattern in history to present day where those that choose truth in the face of liars are persecuted for that truth. The liars get advancements, promotions, etc. while the Truth-Tellers get persecuted, under the weight of the entire system. Sometimes though, the lies are too heavy for the dishonest tyrants to carry, the whole thing comes crashing down, and the Truth-Teller perseveres. This is that story.

The Persecution of the Truth-Tellers Part V.

I made it to my 30’s without hearing of this man. Shameful. No high school curriculum mentioned him either. In fact, what we were taught on Vietnam was real base level, being as big of a conflict as it was. Maybe because I was in a hillbilly school district and everyone was in ‘Support the troops’ mode. It’s no surprise Consciensious Objector was never a vocabulary word US History. “Commie Fag” however….

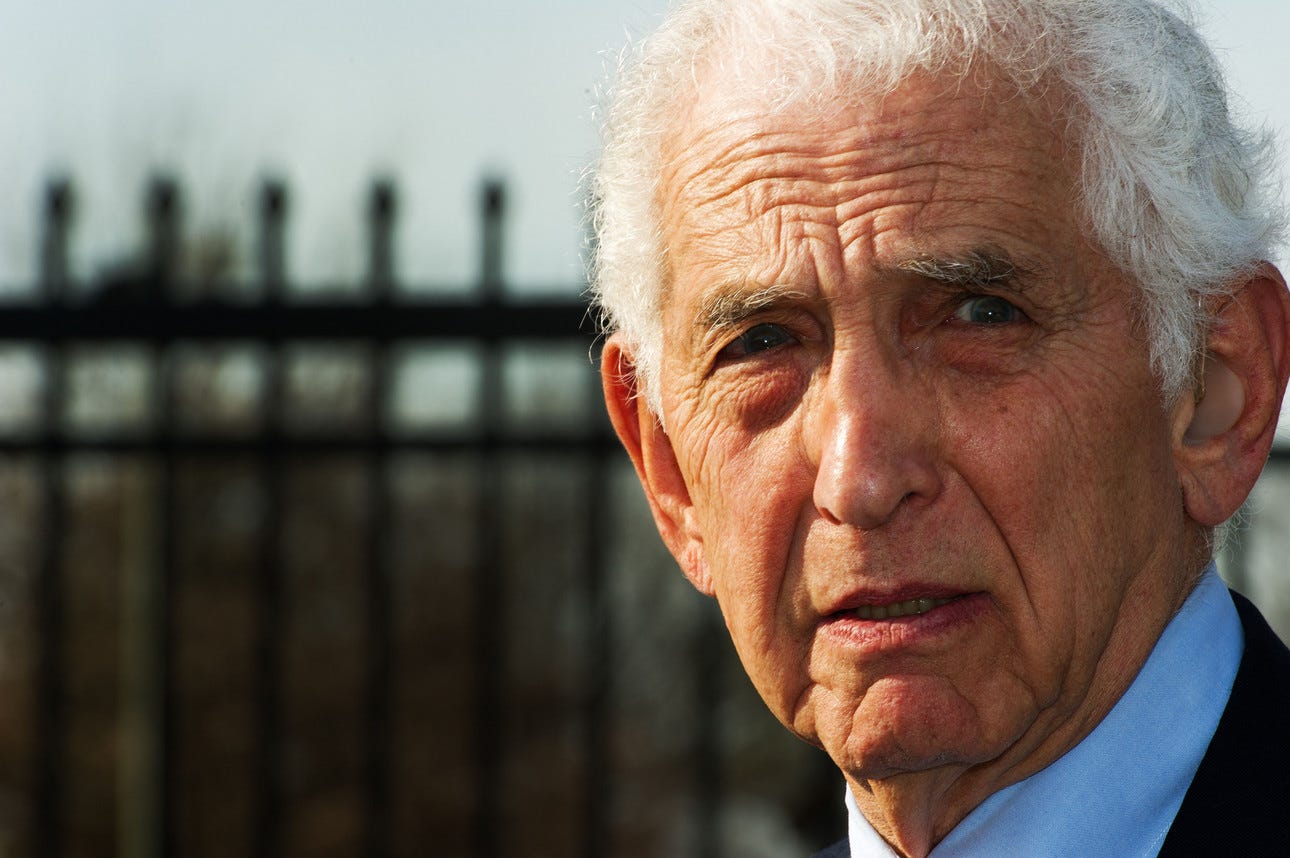

In the future I hope, every child will know the story, of the Pentagon-War-Analyst-Turned-Peace-Activist, my hero, the Great Daniel Ellsberg.

Listening to “Secrets: A Memoir of Vietnam and the Pentagon Papers:” (it’s on Audible for free, anyone who’d like to check it out) and checking out his interviews and reading what others wrote of him I came to see Ellsberg as an American hero. Just as well as we know of Martin Luther King, jr and Abraham Lincoln, Malcolm X or even Marcus Aurelius, we should think of Daniel Ellsberg, just the same.

Diving Right In…

A great place to start, an excerpt from the preface to Secrets:

For eleven years, from mid-1964 to the end of the war in May 1975, I was, like a great many other Americans, preoccupied with our involvement in Vietnam. In the course of that time I saw it first as a problem, next as a stalemate, then as a moral and political disaster, a crime. The first three parts of this book correspond roughly to these emerging perceptions. My own personal commitment and subsequent actions evolved along with these changing perspectives. When I saw the conflict as a problem, I tried to help solve it; when I saw it as a stalemate, to help us extricate ourselves, without harm to other national interests; when I saw it as a crime, to expose and resist it, and to try to end it immediately. Throughout all these phases, even the first, I sought in various ways to avoid further escalation of the conflict. But as late as early 1973, as I entered a federal criminal trial for my actions starting in late 1969, I would have said that none of these aims or efforts—neither my own nor anyone else's—had met with any success. Efforts to end the conflict—whether it was seen as a failed test, a quagmire, or a moral misadventure—seemed no more to have been rewarded than efforts to win it. Why?

As I saw it then, the war not only needed to be resisted but remained to be understood. Thirty years later I still believe that to be true. This book represents my continuing effort—far from complete—to understand my country's war on Vietnam, and my own part in it, and why it took so long to end both of those.

That spoke to, in his elegant way, the different eras of the Vietnam War and how, as they changed, they changed him too. And even at the time he wrote that, he failed at understanding it. The truth, the lies, and the reasons why this war took place. And who/what is to blame. This war was mesmerizing to everyone who came close enough to be confronted by the truth of the thing.

Fifty-Years Later, as Seymour Hersh, his friend, said in a piece on his Substack six months before Dan’s passing, they were still very much confused about the Vietnam war and had a mutual obsession with it. Sy Hersh illustrates the beautiful friendship they had together:

I think it best that I begin with the end. On March 1, I and dozens of Dan’s friends and fellow activists received a two-page notice that he had been diagnosed with incurable pancreatic cancer and was refusing chemotherapy because the prognosis, even with chemo, was dire. He will be ninety-two in April.

Last November, over a Thanksgiving holiday spent with family in Berkeley, I drove a few miles to visit Dan at the home in neighboring Kensington he has shared for decades with his wife Patricia. My intent was to yack with him for a few hours about our mutual obsession, Vietnam. More than fifty years later, he was still pondering the war as a whole, and I was still trying to understand the My Lai massacre. I arrived at 10 am and we spoke without a break—no water, no coffee, no cookies—until my wife came to fetch me, and to say hello and visit with Dan and Patricia. She left, and I stayed a few more minutes with Dan, who wanted to show me his library of documents that could have gotten him a long prison term. Sometime around 6 pm—it was getting dark—Dan walked me to my car, and we continued to chat about the war and what he knew—oh, the things he knew—until I said I had to go and started the car. He then said, as he always did, “You know I love you, Sy.”

This is a story of journalism, a story of justice and a reminder of what the powerful will do if no one is willing to stand up to them and hold their feet to the fire. In the last few years institutions of higher Ed and Corporate press, some of the same involved in this story have called for the rejection of the “Pentagon Papers Principle” in the current “Age of Misinformation”. This is bullshit. As the Government gets stronger and stronger there’s never been a more important time to follow this principle. It should be an amendment to the Constitution and the 11th Commandment, “thou shalt turn over classified documents that expose war crimes or Official lies to the people.”

This story is what happens when a man of morality, a Truth-Teller, lands in an immoral institution. Unfortunately, the immoral institution is the center of American power.

Enough of this convoluted bullshit, here’s the story.

His First Day

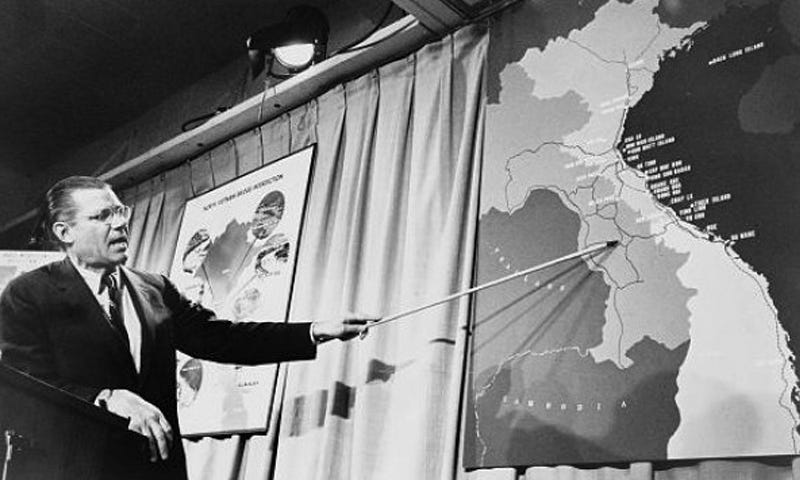

August 4th, 1964, Daniel Ellsberg’s 1st day of work at the Pentagon, he was there for the original lie of the VietnamWar:

I began my first full-time employment in the Pentagon working under Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, my very first day on the job all hell broke loose. A courier came running in with a flash cable saying that American warships were under attack in the Tonkin Gulf off the coast of North Vietnam, and I was getting these because my boss was already down the hall with McNamara picking targets to retaliate against in North Vietnam. Minute after minute more cables came in, three Torpedoes have been fired, Seven, ‘we are taking evasive action.’ At about 1:30AM our time, comes new cables from the Commodore of the two ships, “hold everything in effect, uh, all previous reports of torpedoes are in question.”

What seemed like an attack now looks to be a false alarm! Based on this incident McNamara called for Congress to pass the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution to retaliate for the “attacks” on the American war ships, behind the scenes something else was taking place:

Within days it became clearer and clearer that there had been no attack.

President Johnson was determined to prevent a communist victory in South Vietnam, he twisted the facts of the Tonkin Gulf to persuade Congress to give him unlimited authority to use Military force, he then launched a war that would last eleven more years.

Senator Fulbright:

I accepted the story given to us by the President, Mr. McNamara, and Mr. Rusk. And I believed General Wheeler. I had no reason, at that time and under those circumstances, to doubt the validity and truthfulness of this whole operation.

“No Wider War”

President Johnson claimed:

We still seek, “No wider war”.

Ellsberg, behind the scenes, seen something different:

“No wider War?” As I found out, day by day in the Pentagon, that was our highest priority, preparing a “wider War” which expected to take place immediately after the election.

Johnson:

It's a war that I think ought to be fought by the boys of Asia to help protect their own land and for that reason, I haven't chosen to enlarge the war.

Ellsberg:

And that was a conscious lie, we all knew that inside the government, and not one of us told the press, or the public, or the electorate during that election, it was a well-kept secret by thousands and thousands of people including me.

Let us Rewind a Little

Born in Chicago in 1931, Dan experienced a terrible loss at fifteen. In the summer of 1946, his family went on a road trip from Detroit to Denver, home to both of Ellsberg’s parents, for a party in honor of Adele, his mother. To get there in time, they would have to drive almost nonstop. On the afternoon of July 4, 1946, after a picnic lunch, Harry Ellsberg got behind the wheel, already exhausted from driving most of the previous night. Dan sat on the floor behind his father while his mother stretched her legs across the back seat. His sister sat beside her father in the front. As they headed toward Des Moines, Iowa, Dan’s father fell asleep at the wheel. They veered into a sidewall over a culvert, sheering off the right side of the car. Dan’s sister and mother were instantly killed. He and his father survived, though Dan went into a coma and suffered a serious broken leg. His relatives insisted that he be treated at a hospital despite his father’s objection.

According to the Ellsberg Archive Project for UMass Amherst:

Dan believed it produced two reactions, at least subconsciously. One was the feeling that he “owed a life” because he had lived while his sister and mother had not. The other, was a vigilance toward figures of trusted authority, like his father, who might “fall asleep at the wheel” in ways that could lead to catastrophe.

Ellsberg was great in school, he earned a scholarship to Harvard University, where he studied Economics, he did a stint at the University of Cambridge. After a year of graduate work in Britain he enlisted in the Marines, where he gained an interest in government and defense. Ellsberg being very capable, landed a position in the Pentagon and the RAND Corporation, where he focused on nuclear strategy and crisis decision-making.

However, his direct experience with the Vietnam War, first as a state department official and then on the ground in Vietnam, when he volunteered to go back to the war zone, caused him to almost immediately start looking to do everything he could to de-escalate the war.

His tenure at RAND and subsequent roles in the Pentagon under Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, and reputation for decision-making brought Ellsberg into the inner circles of defense policymaking. He contributed to high-level reports and participated in critical discussions on nuclear strategy, gaining insight into the complexities of government decision-making and the often-opaque processes behind them.

Ellsberg could hear what Mcnamara was telling the public at press conferences and knew that what he was saying publicly was way different than what was he was saying privately.

One time, after arguing with a colleague about how much worse things were getting, Mcnamara called in Dan to settle the dispute and Dan went over the data points, all of them pointing to the war getting worse, not better, which is what Mcnamara also believed. They all were in agreement. Things were worse. The following week at a press briefing on the war, Mcnamara spoke to the people:

You asked whether I was optimistic or pessimistic today, I can tell you that military progress in the past 12 months has exceeded our expectations, I'm very encouraged by what I've seen in Vietnam, in all respect things are better now.

Dan thought to himself:

I hope I’m never in a job where I have to lie like that.

Behind closed doors Mcnamara was very wary about how things were going and was considering pulling back and leaning more towards a political settlement. Johnson rejected this. Mcnamara could see as the public sees it now, to be a blunder, a tragic failure, this was his view in 1966. Remember that the war didn’t end until 1975.

The Study

In June of 1967, McNamara ordered a comprehensive study within the Pentagon on the history of U.S. involvement in Vietnam, he went to the RAND Corporation and recruited the people there who did historical studies, and had expertise in the war, one of the people asked was Daniel Ellsberg:

My involvement in the study would change my life and change history in ways I couldn't have imagined.

The Pentagon Papers Study was classified as top-secret, and every page of every study, was separately classified as top-secret, because they considered the mere existence of the study to be top-secret, since the person we were trying to keep it from was not the Vietnamese, they would not have cared at all, or the Russians or the Chinese, they needed it hidden from Lyndon Johnson himself. Mcnamara feared LBJ, if he learned of the study he would put a stop to it. Johnson knew that Mcnamara had some doubts about the war, and believed there was a group in the Pentagon determined to get us out of Vietnam and would consider the study as that.

President Johnson:

I don't want a man in here to go back home thinking otherwise. We are going to win!

Secretary Mcnamara wasn’t as confident.

In1967, He wanted to pull back on the bombing and reach a “political settlement”, a settlement that looks good politically but not a win. This was totally rejected by LBJ.

Until the Tet Offensive.

In late January, 1968, during the lunar new year (or “Tet”) holiday, North Vietnamese and communist Viet Cong forces launched a coordinated attack against a number of targets in South Vietnam. The U.S. and South Vietnamese militaries sustained heavy losses before finally repelling the communist assault.

This was terrible for the Johnson Admin, more so for the families of the lost, but politically it put a damper on the public perception of the war. We lost 2,600 US Soldiers, 10,127, N. Vietnam/Vietcong lost 60,000; A civilian loss of 7,721. This was a huge blow. When General Westmoreland called for more troops to be sent, it was leaked to the New York Times and landed on the front page. They were requesting 206,000 more troops which blew up in debate on the Floor of Congress.

Senator Wayne Morris D-Oregon

Well, we agree on one thing, they can be badly misguided, and you and the President, in my judgment, have been misguiding them for a long time in this war.

Not only the public was losing faith.

CAST YOUR WHOLE VOTE

Dan seen this as a huge escalation in the war. Because of this he would make his first act of Civil Disobedience by contacting Neil Sheehan at the New York Times and leaking a report saying:

The Central Intelligence Agency had concluded that the enemy's strength in South Vietnam at the beginning of its winter-spring offensive was significantly greater than United States officials thought at the time.

End of August 1969, Dan finds himself at the Campus of Haverford, a Quaker college near Philadelphia, to attend the Triennial Conference of the War Resisters' International (WRI). A passage from Henry David Thoreau's essay "On the Duty of Civil Disobedience" bouncing around in his head:

Cast your whole vote, not a strip of paper merely, but your whole influence. A minority is powerless while it conforms to the majority; it is not even a minority then; but it is irresistible when it clogs by its whole weight.

My translation, act with the full weight of your convictions. Every bit of the influence you have, use it, and crush your adversary. Dan came to the WRI to find out what it meant for him.

The following is from his memoir, the time is late August, 1969, Secrets:

Many things had happened during those sixteen months that should have made a difference and had not: a presidential election campaign that had begun with the war as the central issue; a complete change of party and administration; at the onset of the new administration, a thorough reexamination of alternative options and a questioning of the bureaucracy; the opening of negotiations with Hanoi.

Not one of these, or any other aspect of normal politics, seemed to have brought extrication any closer, despite an electorate that expected it and was obviously anxious for it. If I was ready to change my own relation to the situation, ready even to change my life, there was reason for it.

At the Conference:

My knowledge of such people still came almost exclusively from media accounts, overwhelmingly negative, in which they were presented as being, in varying degree, extremist, simplistic, pro-Communist or pro-NLF, fanatic, anti-American, dogmatic. I went to Haverford in part to find out if these labels were accurate. None of these was a trait I wanted to be associated with. (In coming years, as a price of joining in nonviolent resistance to the war, I heard all these terms applied to me.)

What he found was none of the sort. Dan explains this in the following:

The War Resisters' International, of which the War Resisters League(WRL) was the American branch, had begun after World War I as an association of conscientious objectors, at a time when few countries formally recognized that status. In the twenties it had adopted a Gandhian perspective and now furthered a broad range of nonviolent liberation struggles, but it had kept its pacifist premises.

I told Randall Kehler, head of the San Francisco WRL branch and one of the conference organizers, that I believed I couldn't join WRL because, as I understood it, that involved signing a pledge to refuse participation in all wars, all of which were regarded as crimes against humanity. Despite Vietnam, and my increasing tendency to look skeptically at the claims of any particular war to be "just," I told Kehler, I still thought (as I do today) that violent self-defense was justified against aggression, like Hitler's. Kehler told me he shared similar reservations. “I've never signed that pledge,” he said. He asked others standing around us and found that most of them hadn't either. Their pacifism was non-dogmatic, evolving and exploring, with a considerable recognition of uncertainties and dilemmas.

This was nothing like the media led him to believe. I’m going to continue quoting directly from the book here because the rest of this conference was a very real time that should be quoted, not summarized.

For Daniel Ellsberg, and his life, nothing would be the same.

These antiwar activists shared an assumption accepted by nearly all segments of American society over the sixteen months since Hanoi had accepted Johnsons proposal for open negotiations on April 3, 1968.

They believed Nixon was pulling out of the war. They believed the only question that remained was “the tempo of withdrawal... in this fag end of a long and beastly war.” (How quickly they withdrew, and got the troops home) Dan knew this assumption was wrong. He learned the previous week before the conference that Nixon had no intention of ending this war.

In my head as I went to Haverford was Halperin's flat prediction to me in Washington: "This administration will not go into the election of 1972 without having mined Haiphong and bombed Hanoi." And Vann's disclosure “that there would still be tens of thousands, at the least, of U.S. troops in South Vietnam at the end of 1972.” I could not reveal at the conference what I knew. It had been revealed to me on an unusually confidential basis.

On Tuesday evening, I finally had a chance to talk with Bob Eaton, the night before he was to go to prison two years after telling his draft board that he would no longer cooperate with the Selective Service System. Since then, in addition to his voyage on the Phoenix to North and South Vietnam, he had worked on the pacifist networks AQAG (A Quaker Action Group) and The Resistance, supporting non-cooperation with the draft. In September 1968 he had been one of the members of the WRI who had risked imprisonment in Eastern Europe, conducting protests against the invasion of Czechoslovakia. A troublemaker. Yet given the prevailing belief that the war was in the process of ending, Eaton's impending prison sentence probably seemed to many of those present almost an *anachronism. He had alluded to this attitude in his talk on the first day. It addressed resistance to militarism in large part, rather than to the Vietnam War, because, as he said, “The basis of GI organizing now is, no one wants to be the last guy shot in a war.... That's also a problem for the Resistance, because I think no guy wants to be the last guy to go into prison resisting a particular war.”

They were paying mind to all conflicts as a whole instead of only Vietnam. They believed Vietnam was over but thanks to Dan we know otherwise.

*An anachronism is a person, thing, or event that is placed in a historical time where it does not belong.

Dan struggles to understand Bob Eaton’s dedication to the cause. He feels there’s no way he would be out here when he’s going to prison in the morning. Bob still attended every meeting, and afterwards Dan found him, beer in hand talking long-range strategy, and tactics for transforming America.

Dan begins a dialogue within himself. He’s afraid to be caught here. Afraid to lose his security clearance. Afraid to appear as a loon. But something else tugs at him inside. He knows this is the right place to be.

The conference was holding no meetings the next morning, Wednesday, so that members could go into Philadelphia to circle the Post Office Building in a vigil while Eaton was being sentenced inside. Buses and cars had been arranged to take us all in. I tried to think of an excuse to get out of it that the others could accept, but it wasn't easy. I was embarrassed by my own reservations. What was the problem? A man I admired was being sentenced to prison for an act of conscience. He and his friends wanted a show of solidarity for straightforward political reasons and perhaps because it would make him feel better. There was an invitation to join that, in the company of one of the heroes of the century, *Pastor Martin Niemoller*, and others I admired no less. How could I not go? The fact is, it WAS a problem for me. It was a combination of the small risk of my being discovered and an undeniable feeling I had that there was something demeaning about the whole thing. What if the press or the police or the FBI took pictures of us? What if my name was mentioned in the media and got back to Washington or Santa Monica? I knew what my associates in either place would think: that I had gone out of my mind. They would see it as a total sacrifice of dignity and of elite insider status, for nothing, for an action of no consequence, no effectiveness, nothing worth taking the smallest risk of losing access to secret information and to people of influence. It could be explained in no other way than a fit of madness. I could hear their reaction in my head, and I couldn't really argue with it. This was hardly the place, or the way, to announce to Rand, the Pentagon, and the White House that I was joining the public opposition to the war. To their war. But Bob Eaton was going to prison, and I couldn't think of a reason I could give his friends for refusing to see him off. I thought of saying I was sick, but the conference had two days to go, and I couldn't keep that up plausibly. So, on an August morning in 1969, while Martin Niemoller and Devi Prasad were inside with Bob, making statements to the court on his behalf, I found myself on a sidewalk in downtown Philadelphia in a line of variously dressed peaceniks, some of them carrying placards, others handing out leaflets. I walked along with them, at first with great misgivings. The sidewalk outside the Post Office Building in Philadelphia that morning was a long way from the Executive Office Building in Washington, where I had spent February that same year writing memos for the president. Both were places perhaps for “speaking truth to power,” the Quaker phrase for vigils and acts of “witness to peace” of the kinds we were engaged in that morning. But you could not do that in both places, not if you wanted to be welcomed back to the NSC. You could not have the opportunity to draft top secret commentaries for the president on Vietnam options, or give his national security assistant confidential advice, if you were the sort of person who spent days off from work demonstrating in support of draft resisters on street corners in Philadelphia. You could not have the confidence of powerful men and be trusted with their confidences if there was any prospect that you would challenge their policies in public in any forum at all. That was the unbreakable rule of the executive branch. It was the sacred code of the insider, both the men of power and those, like me, privileged to advise and help them. I knew that as well as anyone. I had lived by that code for the last decade; it was in my skin.

I was, it seems, in the process of shedding that skin on that morning. Before I had grown a new one. I felt naked — and raw. My memory is of feeling chilled on a gray, wintry day; I have to remind myself that it was Philadelphia in August. But no one after all was noticing me. There was no press, no police. People passed by incuriously, mostly without pausing to read our placards. Some accepted the leaflets we handed to them; others didn't or handed them back. Passersby looked briefly at us or kept their eyes straight ahead, as they would glance, or not, at panhandlers or nowadays at the homeless.

*Martin Niemoller was captured in WWII by the Nazi Regime after being silent earlier in the war when the Nazi’s were oppressing those who were convenient for him. Famously, in his post-war statement he refers to this and why you should never be silent!

First they came for the socialists, and I did not speak out—because I was not a socialist.

Then they came for the trade unionists, and I did not speak out—because I was not a trade unionist.

Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out—because I was not a Jew.

Then they came for me—and there was no one left to speak for me.

—Martin Niemöller

Dan spent the evening in solidarity with his new friends, passing out flyers, holding up placards for the public to see. The paranoia was fading and he was really starting to get into it. To enjoy it. He was growing new skin.

My mood had changed. I was feeling unaccountably lighthearted. Around noon the word was passed that Eaton had been sentenced and had been taken off to a cell. The judge had listened respectfully to the statements by Pastor Niemöller and the others and had then given Bob the three-year sentence he had expected. We went back to the conference.

Something very important had happened to me. I felt liberated. I doubt if I could have explained that at the time. But by now I have seen this exhilaration often enough in others, in particular people who have just gone through their first act of civil disobedience, whether or not they have been taken to jail. This simple vigil, my first public action, had freed me from a nearly universal fear whose inhibiting force, I think, is very widely underestimated. I had become free of the fear of appearing absurd, of looking foolish, for stepping out of line.

One other thing had happened, though again I didn't fully recognize it till later. By stepping into that particular vigil line, in solidarity with Bob Eaton and in company with others whose views I shared and whose lives of commitment I respected, I had stepped across another line, an invisible one of the kind that recruiters mark out on the floor of an induction center. I had joined a movement.

On the next day, August 28, 1969, the final day of the conference, I heard a talk by Randy Kehler during the last session in the afternoon. Alone out of all the presentations at the conference, Randy's talk was personal. He said he wanted just to share some things on his mind.

I hadn't had a chance to talk with Kehler at any length earlier, but he had made a good impression on me. He listened carefully, responded thoughtfully and with good sense. Of the many younger American activists I had met at the conference, he was one I wanted to see more of; I had decided to arrange to visit him in San Francisco soon. He had a very simple and direct manner, along with warmth and humor. He was a very appealing person.

I was somewhat surprised, when he began, to hear that we had gone to the same college, that he was, like me, a transplant from Cambridge to California. I remember thinking, Well, here's a credit to Harvard! And one who learned some things after he left. I then heard for the first time about the path that had led him to head the War Resisters League office in San Francisco.

“When I finished Harvard College and three weeks of graduate school at Stanford, I was out on the West Coast. I was involved in a demonstration in which hundreds of men and women were sitting in the doorways of the [Oakland] induction center trying to pose a question to all those going through the doors, to be inducted or to take their physicals. We wanted that question to be very real, and not just a matter of words, so we actually placed our bodies in those doorways.

“Well, that was a very new experience for me and one that really changed the whole course of my life. Before I knew it, I was behind bars with that same couple of hundred people, and I found a community of people for the first time that not only….were committed to each other, but a community of people that were committed to something larger than themselves, something probably more noble, more ideal, than anything I had been involved in after twenty-two years of public education. And it was as a result of that demonstration and that time I spent in jail with those people that I saw a very real alternative to the kind of life I was leading, which made me leave school and go to work for the WRL in San Francisco.”

He talked about nonviolence as a way of life. . . . What I remember most vividly is not the content of what he had said so far but the impression he made on me as he spoke without preparation from the platform. Listening to him was like looking into clear water. I was experiencing a feeling I don't remember having had in any other circumstances. I was feeling proud of him as an American. . . . .

As a matter of fact, it was hard to imagine anyone whose looks, manners, and virtues were more American than Randy Kehler’s. That was what was recalling to me a sense, not so familiar lately, of national pride. The auditorium was filled with people from all over the world. I was thinking as he spoke, I'm glad these foreign visitors are having a chance to hear this. He's as good as we have.

At that moment he brought me out of my reverie by saying something with a catch in his voice. He had just said, "Yesterday our friend Bob went to jail.” He had to pause for a moment. He cleared his throat. Evidently he had tears in his eyes. He smiled and said, “This is getting to be like a wedding we had a month ago, when Jane and I were married on the beach in San Francisco, because I always cry a lot.” After a moment he went on, in a steady voice. “Last month David Harris went to jail. Our friends Warren and John and Terry and many others are already in jail, and I'm really not as sad about that as it may seem. There's something really beautiful about it, and I'm very excited that I'll be invited to join them very soon.”

Again he had to pause. The audience seemed taken by surprise. A scattering of applause began, then suddenly swelled, and people began to stand up. But he was going on, and people stopped applauding, continuing to rise, in silence. “Right now I'm the only man left in the San Francisco WRL office because all the others have gone to prison already, and soon, when I go, it will be all women in the office. And that will be all right.... I think I know that, and I think Bob and David know that, but there's one other reason why I guess I can look forward to jail, without any remorse or fear, and that's because I know that everyone here and lots of people around the world like you will carry on."

The whole audience was standing. They clapped and cheered for a long time. I stood up for a moment with the rest, but I fell back into my seat, breathing hard, dizzy, swaying. I was crying, a lot of people must have been crying, but then I began to sob silently, grimacing under the tears, shoulders shaking. Janaki was to talk next, but I couldn't stay. I got up — I was sitting in the very last row in the amphitheater — and made my way down the back corridor till I came to a men's room. I went inside and turned on the light. It was a small room, with two sinks. I staggered over to the wall and slid down to the tile floor. I began to sob convulsively, uncontrollably. I wasn't silent anymore. My sobbing sounded like laughing, at other times like moaning. My chest was heaving. I had to gasp for breath.

I sat there alone for more than an hour without getting up, my head sometimes tilted back against the wall, sometimes in my hands, without stopping to shake from my sobbing. I had never cried like this before except, more briefly, when I learned that Bobby Kennedy was dead. A line kept repeating itself in my head: ‘We are eating our young!’

I had not been ready to hear what Randy had said. I had not been braced for it. When he mentioned his friends who were in prison and remarked that he would soon be joining them, it had taken me several moments to grasp what he had just said. Then it was as though an axe had split my head, and my heart broke open. But what had really happened was that my Life had split in two!

‘We are eating our young,’ I thought again, sitting on the floor of the men's room in the second part of my life. On both sides of the barricades we are using them, using them up, “wasting” them. This is what my country has come to. We have come to this.

The best thing, that the best young of our country, can do with their lives is to go to prison. My son, Robert, was thirteen. This war would still be going on when he turned eighteen. (It was.) My son was born to face prison. Another line kept repeating itself in my head, a refrain from a song by Leonard Cohen: "That's right, it's come to this, yes, it's come to this. And wasn't it a long way down, ah, wasn't it a strange way down?"

After about an hour I stopped sobbing. I stared blankly at the sinks across from me, thinking, not crying, exhausted, breathing deeply. Finally I got up and washed my face. I gripped the sink and stared at the mirror. Then I sat down on the floor again to think some more. I cried again, a couple of times more, briefly, not so violently. What I had just heard from Randy had put the question in my mind, What could I do, what should I be doing to help end the war, now that I was ready to go to prison for it?

What Can I Do?

In August of 1969, before or after the conference at Haverford, I’m unsure. Dan read the earliest parts of the Mcnamara study for the first time. Seeing the war from its beginning he knew what he had to do.

It changed my whole sense of the legitimacy of the war. What I learned was that it was an American war from the start. President Truman financed the French to retake its former Colony, even though he knew the French were fighting a national movement that had the support of the people. Eisenhower supported a brutal dictator in cancelling elections called for by the 1954 Geneva accords. So we opposed elections while pretending to support democracy.

Kennedy lied to the public and to Congress saying we would need only advisors, even though his own military experts told him that South Vietnam would be lost without an immediate commitment of American combat units.

I now saw that Johnson was continuing a pattern of presidential lying. Each president wanted to avoid losing Indochina to Communism on his watch. It wasn't that we were on the wrong side. We were the wrong side! It was a crime from the start, carried out by four presidents as revealed in this study. And now a fifth president was doing the same, with no end in sight. The hundreds of thousands we were killing was unjustified, homicide, and I couldn't see the difference between that and murder. Murder that had to be stopped.

Nixon to Kissinger: “Henry, you don't have any idea, the only place where you and I disagree is with regard to the bombing. You're so concerned about the Civilians. And I don't give a damn. I don't care.

Kissinger: “I'm concerned about the Civilians because I don't want the world to be mobilized against you as a butcher.”

His life had changed. He was ready to cast his whole vote.